Most of the murder cases we have documented appear to be of girls under the legal age of majority (less than 18). This points to a legal loophole that allows girls to be handed back their guardians, who have no hesitation in murdering them in cold blood, supposedly to “erase shame.”

The amended Juvenile Welfare Act No. 76 of 1983, stipulates that people under the age of 18 must be returned to their guardians. Article 23 of the law give police the power to search for runaways from their families who are under the legal age, and also to return to their families those the police find in places of delinquency, such as cafes, cinemas, discos, and bars. Article 24 of the same law stipulates that a minor is considered a fugitive if they leave their guardian’s home without a legitimate reason.

Amnesty International’s report, which was issued in July 2024, discusses a similar case of two sisters – one 17 and the other 19 – who were killed in Kurdistan Region. Their bodies were found after they had been handed over to their father, who had signed pledge that was not legally binding, according to the report.

Lawyer and judicial expert Mohammed Al-Qadi criticises the executive authorities for not taking seriously the fate of runaways or even looking into the reasons why they flee, only to be stopped by the police and handed over to the murderer.

Director of Community Police in the Ministry of Interior, Brigadier General Ali Ajami, did not deny that girls who run away are handed back to their guardians, but he insisted that the police acted cautiously and confidentially and according to procedures that the judiciary are informed of, so as to safeguard the family structure as well as the lives of the girls.

The response of the tribes

We reached out to the leaders of a number of tribes, but most refused either to talk or to comment on the findings if this investigation.

Sheikh Adnan Al-Danbous, head of the Kenana clan and a former member of the Iraqi parliament, told us that these crimes are not talked about in Iraq, because of the religious and tribal nature of Iraqi society.

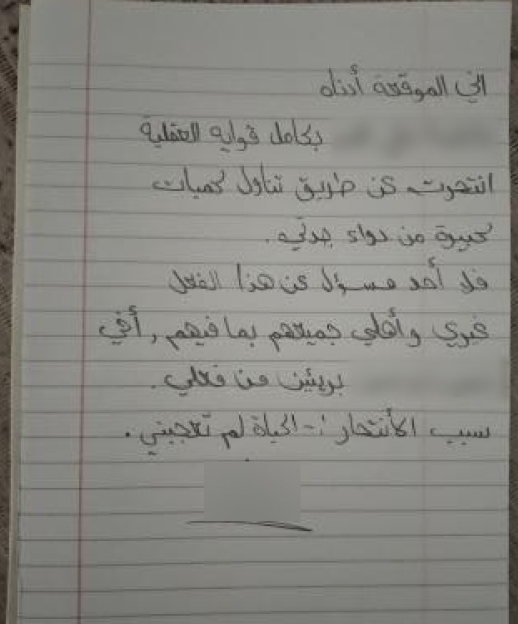

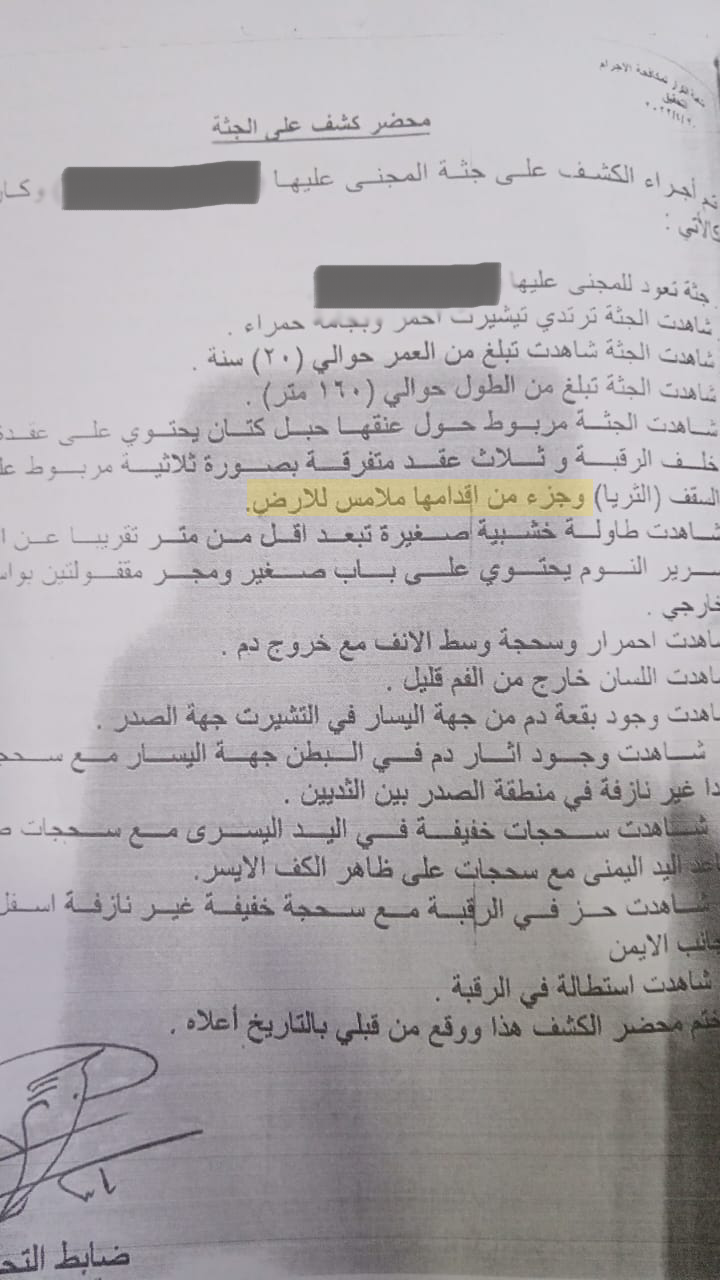

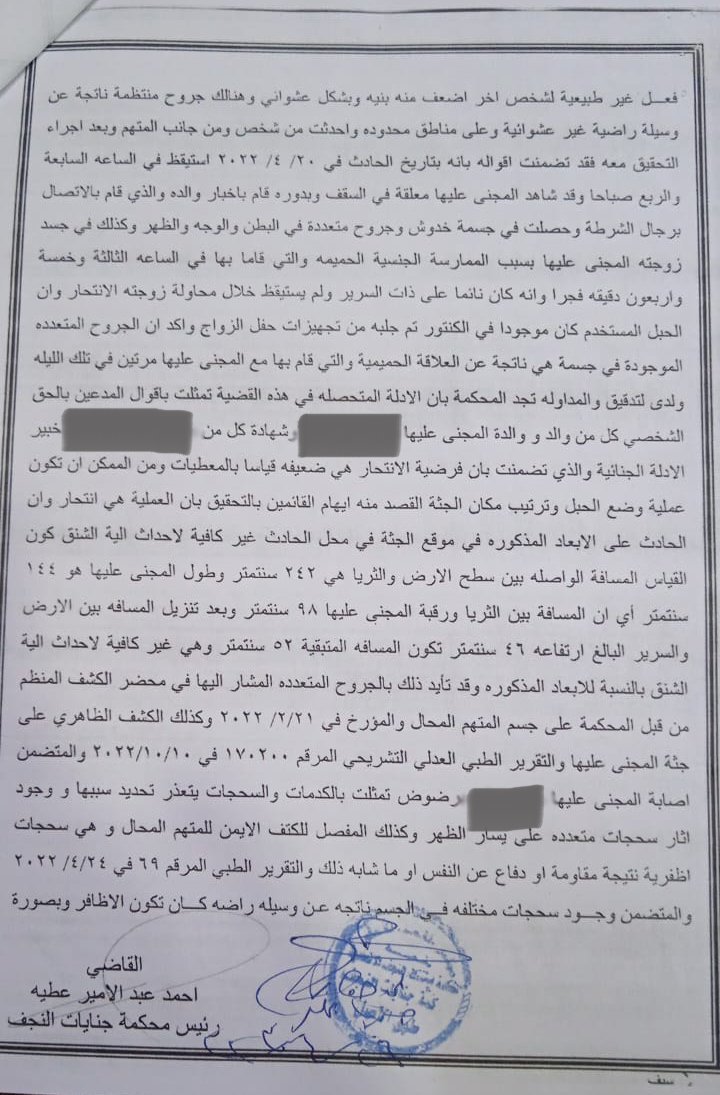

He said that the victim is usually killed merely on “suspicion,” without any evidence being presented or investigation undertaken, and sometimes the girl is killed in such a way as to not attract attention. Among the examples he gave were girls being burned or electrocuted, or poisoned so as to make the crime look like suicide. On the question of the secret graveyards, Al-Danbous preferred to say nothing, because of the sensitivity of the issue.

Meanwhile, Sheikh Bassem Al-Hajami, Secretary-General of the Arab Tribal Cooperation Council, brought up the question of what he called “the horror of marital infidelity or adultery,” which he said was an issue of crucial importance in an Oriental society, governed principally by tribal custom and religious teachings second.

He categorically denied that there were any hidden or tribal graveyards where victims were buried, insisting that “honour killings” happened the world over, and that in Iraq the rates were actually lower than the average.

But the former spokesperson for the Iraqi High Commission for Human Rights, Ali Al Bayati, made clear that crimes to “expunge shame” were widespread across all of Iraq, and that the country was witnessing a sharp increase in incidence. He pointed out that figures show at least 150 women and girls die each year in honour killings, and that “the actual number is even higher.”

Meanwhile, a report by Human Rights Watch, based on a statement by the UN Special Rapporteur on violence against women, indicates that there were about four thousand honour killings in Iraq between 1991 to 2001.

Activists in numerous rights organisations in Iraq are of the view that the published numbers of murders “on the pretext of honour” are much lower than the actual figure, considering the incidence of other crimes that take place in complete secrecy.